Get Healthy!

Staying informed is also a great way to stay healthy. Keep up-to-date with all the latest health news here.

05 Jul

Teenage Drivers Spend About 21% of Each Road Trip on the Phone

Researchers surveyed more than 1,100 teenage drivers and found cell phones are a big distraction behind the wheel – even though many are aware of the danger to themselves and others.

02 Jul

Top 3 Medical Emergencies At School

A new study identifies three medical emergencies that account for the most EMS calls at schools. Researchers recommend improved training for these target areas.

01 Jul

Childhood Obesity in the U.S. Continues to Rise

A new study finds obesity in kids 2 to 19 years of age increased significantly between 2011 and 2023, and the COVID-19 pandemic was not a main driver.

Is One Type of Water Healthier Than Another? Here’s What Experts Say

Alkaline. Electrolyte. Flavored. Walk down the beverage aisle and you’ll find all kinds of waters promising extra health perks. But are these fancy waters really better for you?

Not really, Tufts University experts say.

“There's no physiological basis that there's some metabolic benefit to these specialty waters over just...

- I. Edwards HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 5, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Hearing Aids Are a Boon To Social Life, Study Finds

Some folks won’t use hearing aids because they’re worried the devices will make them look old or get in the way of their social life.

Nothing could be farther from the truth, a new evidence review says.

Hearing aids dramatically improve a person’s social engagement and reduce feelings of isolation or loneliness, bas...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 3, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Prevent 4th of July Firework Injuries by Taking These Simple Steps

Fireworks are the pinnacle of many Fourth of July celebrations, and while they can be festive and fun, they can also land you in the emergency room if you don’t take proper precautions, experts warn.

About 250 people a day wind up in the ER with fireworks-related injuries in the month before and after Independence Day. More than 75% ...

- Denise Mann HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 3, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Want More Exercise? Go To Bed Earlier, Study Suggests

The age-old “early to bed, early to rise” proverb applies to your daily exercise regimen as well as your health, wealth and wisdom, a new study says.

Folks who get to bed earlier tend to be more physically active every day, researchers reported June 30 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

On av...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 3, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Smartphone-Controlled Nerve Stimulator Returns Golfer To The Links

Avid golfer Robert Knorr found he was no longer able to hit the links last year, due to neuropathy in his legs and feet.

The nerve pain got so bad that Knorr needed a cane — and sometimes a wheelchair — to get around.

But the 69-year-old retired oil company executive has traded that cane for his golf clubs, thanks to a sp...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 3, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Teen Drivers Spend A Fifth Of The Time Looking At Their Smartphone, Study Says

About a fifth of the time, a teenage driver is looking at their smartphone rather than the road or their rearview, a new study says.

Teen drivers spend an average 21% of each trip looking at their phone, according to results published today in the journal Traffic Injury Prevention.

Worse, these weren’t quick glances &m...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 3, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Schools Should Be Prepared For These Three Medical Emergencies

There are three common health emergencies for which all U.S. schools should be prepared, a new study says.

Brain-related crises like seizures, psychiatric conditions or substance abuse, and trauma-related injuries are the three main reasons paramedics respond to schools, according to a new report in the journal Pediatrics.

A...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 3, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Wildfire Smoke Linked To Heart Failure Risk

Wildfire smoke might increase a person’s risk of developing heart failure, a new study suggests.

People had a 1.4% higher risk of heart failure for every 1 microgram per cubic meter increase in their exposure to particle pollution from wildfires, researchers report in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 3, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Could Dairy Be Causing Your Bad Dreams?

Having bad dreams after eating ice cream or cheese? Your stomach may be trying to tell you something.

New research shows that people with worse symptoms of lactose intolerance tended to report more frequent nightmares, NBC News reported.

The research, published July 1 in Frontiers in Psychology, looked at the eating...

- I. Edwards HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 2, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Most Dads Take Two Weeks or Less of Parental Leave, Study Finds

Taking time off work when a baby is born is good for dads and babies alike. But a new study finds that most fathers still don’t take much parental leave — often because they simply can’t afford to.

Just 36% of new dads said they took more than two weeks of leave after their child’s birth, while 64% said they took tw...

- I. Edwards HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 2, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Judge Blocks Layoffs at U.S. Health Department

A federal judge has stopped the Trump administration from implementing more layoffs at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), saying the job cuts likely went against the law.

The decision came Tuesday from U.S. District Judge Melissa DuBose in response to a lawsuit filed by attorneys general from 19 states and the District...

- I. Edwards HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 2, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Tattoos Don't Convey Accurate Impressions Of People, Study Says

Tattoos have become a form of self-expression, a means of telling the world something about yourself.

Unfortunately, observers mostly misread these inky cues and misjudge the personalities of tattoo bearers, a new study says.

Study participants tended to agree among themselves on what they think a tattoo says about someone, but their...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 2, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Sleep Apnea Puts Soldiers In Harm's Way

Sleep apnea could be increasing the risks borne by U.S. soldiers serving on the front lines of combat, a new study says.

Front-line soldiers are far more likely to suffer PTSD, anxiety, depression and injuries if they have sleep apnea, researchers reported recently in the journal Chest.

“This study underscores the grow...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 2, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Livestock Manure Could Be Source Of Antibiotic Resistance, Researchers Warn

Antibiotic resistance is an urgent global public health threat, as more microbes gain the ability to thwart essential bacteria-killing drugs.

And there's a hidden means by which antibiotic resistance is likely increasing, researchers say.

Manure from livestock is a major reservoir for antibiotic resistance genes that could threaten h...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 2, 2025

- |

- Full Page

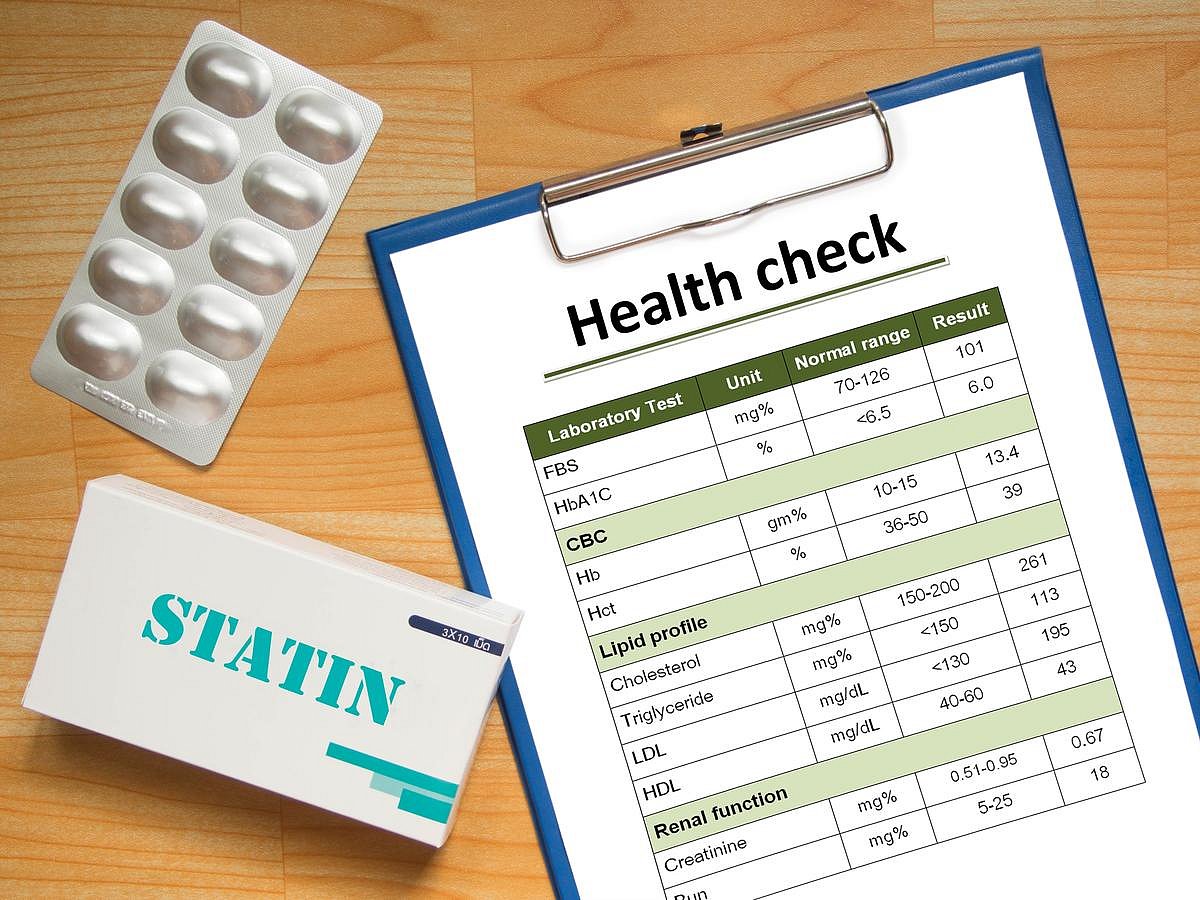

Tens Of Thousands of Heart Attacks, Strokes Could Be Prevented With This Prescription

Tens of thousands of people suffer needless heart attacks and strokes every year because they aren’t taking cholesterol-lowering drugs, a new study says.

More than 39,000 deaths, nearly 100,000 non-fatal heart attacks and up to 65,000 strokes in the U.S. could be prevented if people eligible for statins and other cholesterol-lowering...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 2, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Brainstorming? Avoid The Internet, Study Says

Want to think outside the box?

Avoid the internet, a new study says.

Googling for new ideas can inhibit a group’s creativity during brainstorming sessions, researchers reported June 30 in the journal Memory & Cognition.

Internet searches appeared to stymie the production of clever ideas in groups asked to bra...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 2, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Anger Management Improves With Age In Women, Study Says

Remember your sweet-hearted grandmother, who never seemed out of sorts no matter what nonsense landed in her lap?

That’s a skill, and it improves during a person’s lifespan, a new study says.

Women get better at managing their anger as they age, starting in middle-age, researchers reported today in the journal Menopau...

- Dennis Thompson HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 2, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Trump Administration May Cut Funds to Hospitals Offering Gender Care to Kids

The Trump administration may cut off federal funding to hospitals that provide gender-related treatments to children and teens.

Nine major children’s hospitals recently received letters from federal officials seeking information about procedures such as hormone therapy, puberty blockers and sex-reassignment surgeries, The Wall St...

- I. Edwards HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 1, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Supreme Court Won’t Hear Anti-Vaccine Group’s Free Speech Case

On Monday, the U.S. Supreme Court said it will not hear a case brought by a group once led by U.S. Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. that claimed Facebook censored its vaccine-related content.

The Children’s Health Defense sued Meta Platforms, the parent company of Facebook and Instagram. It claimed the company removed their con...

- I. Edwards HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 1, 2025

- |

- Full Page

Moderna’s New Flu Shot Shows Strong Results in Older Adults

Moderna’s new flu vaccine, based on the same mRNA technology used in its COVID-19 shot, showed promising results in a major trial, the company announced Monday.

The vaccine, called mRNA-1010, was tested in a Phase 3 study in adults aged 50 and older. It worked better than a standard-dose flu vaccine, providing 26.6% more protection a...

- I. Edwards HealthDay Reporter

- |

- July 1, 2025

- |

- Full Page